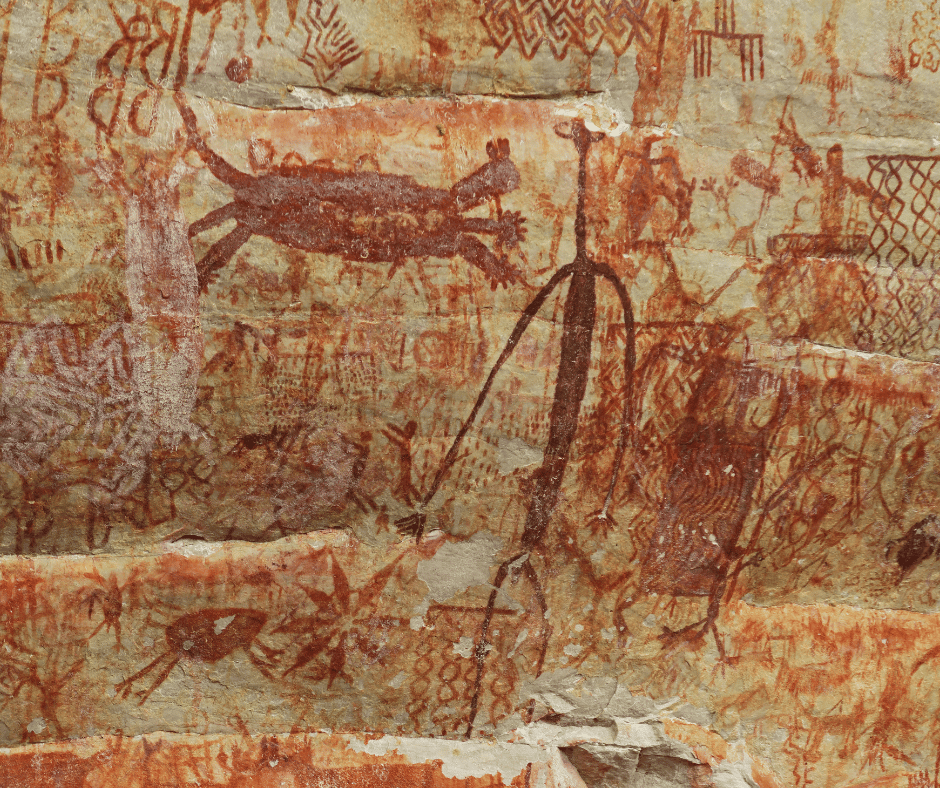

According to a new study, some prehistoric mammals were born almost independent and grew up twice as fast as today’s mammals. This gave them an advantage after dinosaurs became extinct.

The life history of Pantolambda bathmodon (P. bathmodon), a member of the ancient group of herbivores that weighed about a sheep and grew to around the size of a sheep in the post-dinosaur era, was investigated with dental analysis.

P.bathmodon mothers were found to be pregnant for just under seven months, and they bore single, well-developed children with a full mouthful of teeth in the study published in Nature.

The average lifespan of a keto bear is two to three years. At birth, they were undoubtedly mobile, and after only one or two months, they had acquired complete autonomy in their movements.

A team composed of members from the University of Edinburgh, University of St Andrews, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and New Mexico Museum ought to carry out this research.

Professor Steve Brusatte, personal chairman of palaeontology and evolution at the University of Edinburgh’s School of GeoSciences, said: “Some mammals were able to survive the asteroid that knocked off the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. These mammals quickly ballooned in size to fill the ecological niches vacated by T. rex, Triceratops, and other giant dinosaurs.”

“Being able to create big fetuses, which developed for several months in the womb before being born, helped mammals transition from tiny mouse-sized ancestors that lived with dinosaurs to the wide range of creatures, including humans and elephants, that exist today.”

The zinc and barium detected in the teeth revealed crucial life stages of the creatures, including birth and suckling. Although the study’s estimated gestation period seems to match that of today’s similarly sized animals, by comparison this early mammal was discovered to have lived and died more quickly.